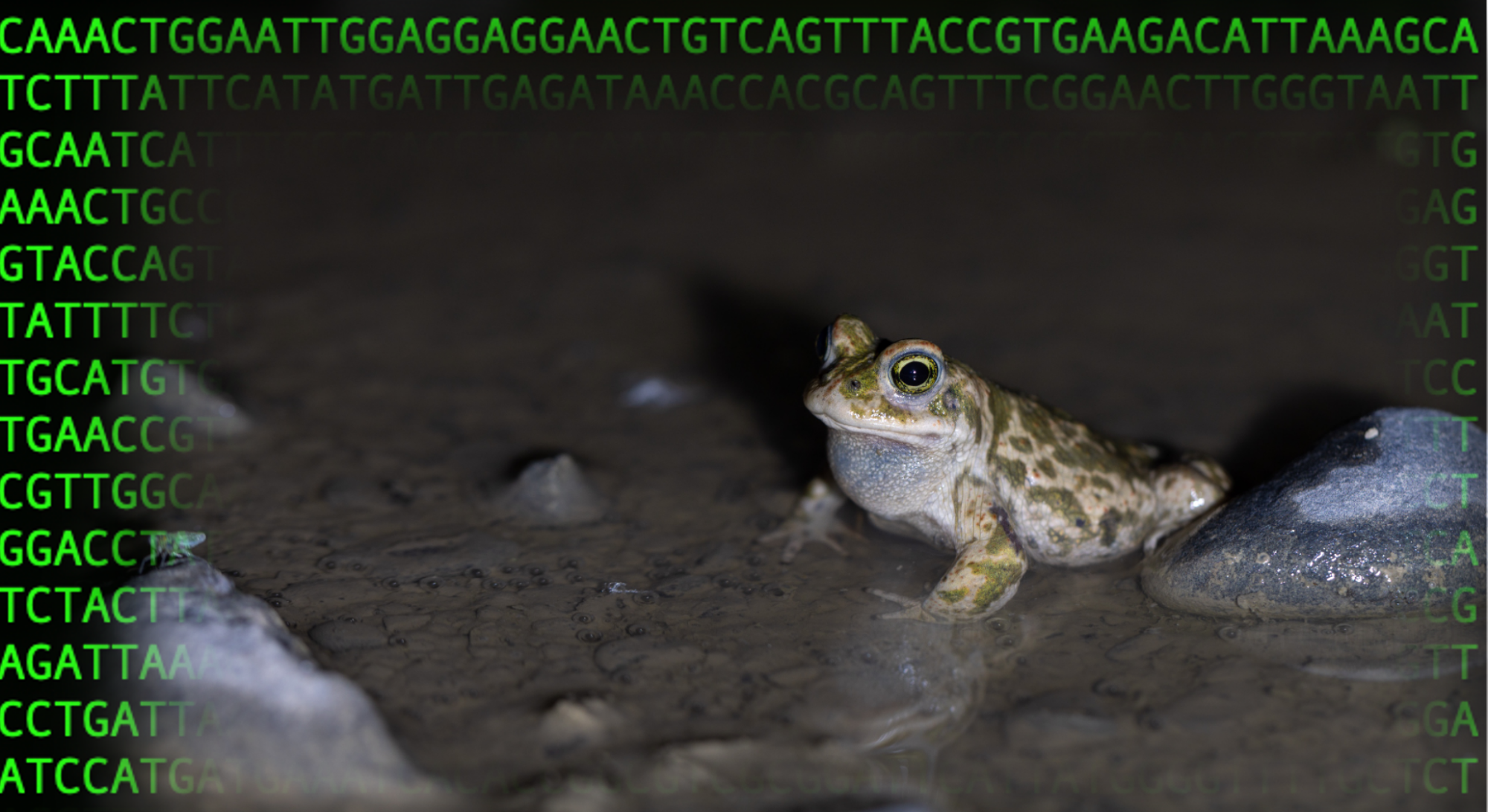

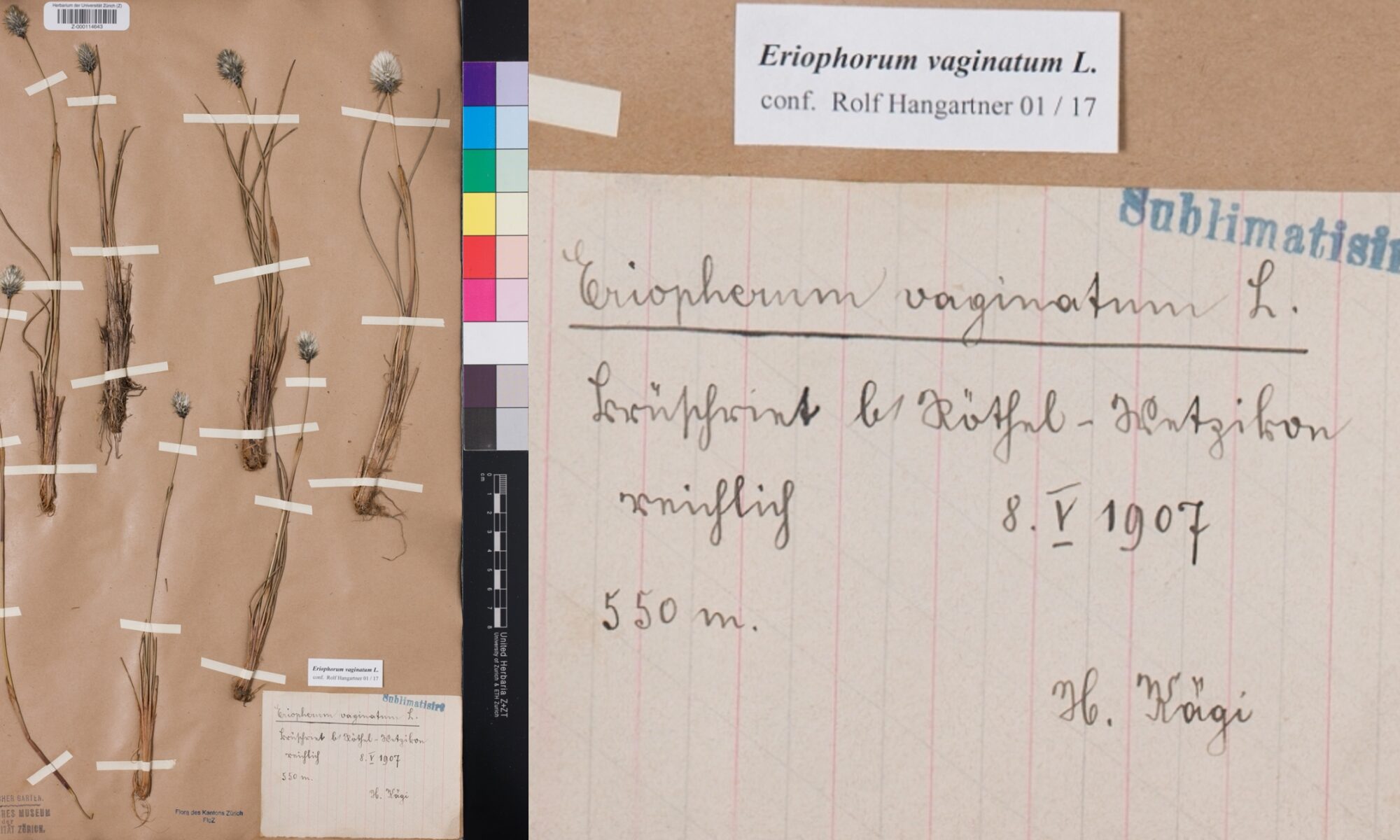

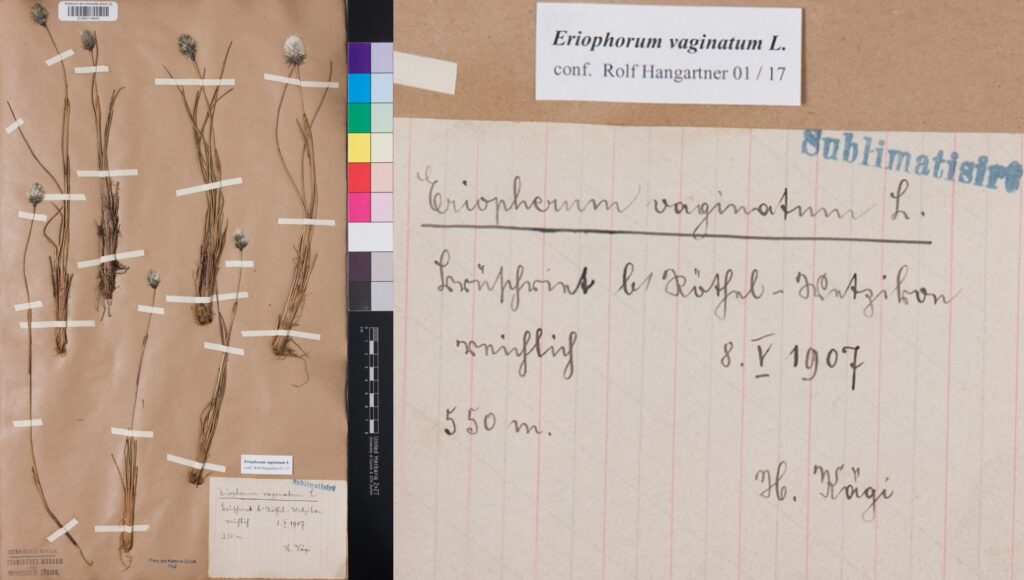

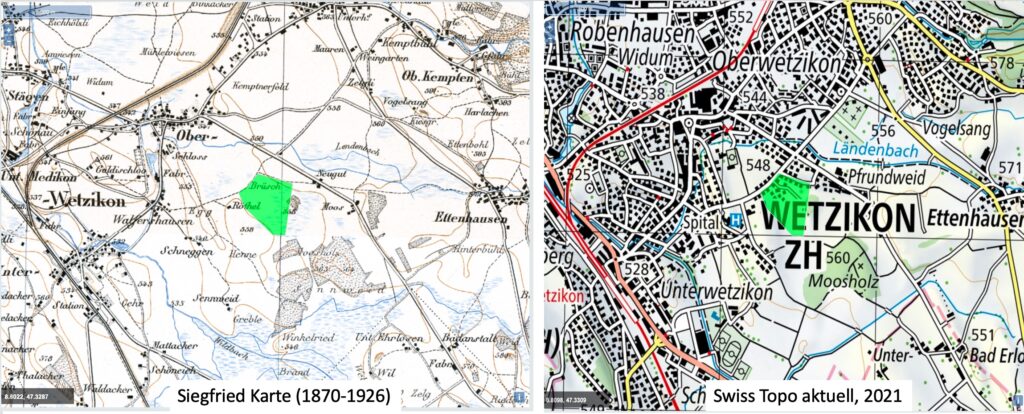

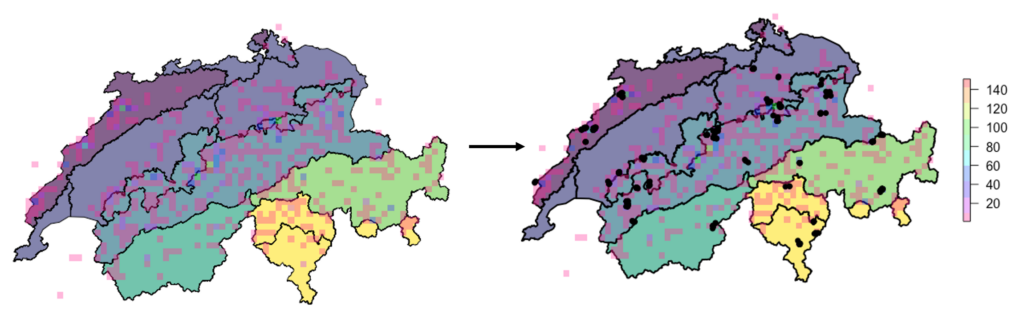

The fieldwork season began this spring. The teams of the Swiss Ornithological Institute started earliest at the beginning of April in Ticino and Graubünden. Since then, 117 yellowhammers have been caught, sampled and released throughout Switzerland. Breeding calls of natterjack toads began at the end of April, a sign for which the staff of the karch had been waiting to begin sampling. However, the search for natterjack toad populations at the planned collection sites have not always been successful and often the collection sites planned as reserves needed to be used. This was due to characteristics of the natterjack toad’s pioneer habitat, which is composed primarily of temporary pools in gravel pits and floodplains, which are not stable long-term. The input of the karch staff, with their knowledge of local natterjack toad spawning areas and ecology, has been invaluable. Thanks to them, spawning areas that are no longer active could be removed from the list of collection sites in advance, and new collection sites could be recorded where necessary. Sampling of the populations of the Carthusian pink and the Hare’s-tail cottongrass has also started. Lastly, depending on the weather, sampling of the False heath fritillary will soon begin. We are curious to see what challenges this particular sampling holds for our experts.